Raju Korti

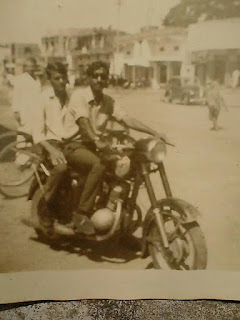

I do not recollect how and when my love for bikes turned into an Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. I suspect the transition had something to do with driving four-wheelers. When I started driving cars some thirty years back, I realised that there was not enough stirring in it to send my adrenaline soaring. I found -- and still feel -- driving four wheelers was no fun, no adventure simply because there was no balancing involved. What's the fun when the car is brought to a halt without those last minutes of anxious wobble? The bike assured a breath-taking and screeching halt almost as effectively as you see in advertisements. Riding a motor-cycle, unlike driving a car, was like wearing a badge of masculinity on the sleeves. If you wonder what provokes this blog, it is a picture posted by an old friend and Indian Express colleague Sharad Rotkar astride a bike with an expression Arnold Schwarzenegger would have envied. But knowing him, I know it was more of an advertisement for Jawa which we all dreamt of having under our butts. Our limited finances, however, made us do peace with the toy Lunas and mopeds. Riding a Jawa or a Bullet happened occasionally when a friend was magnanimous enough to lend it for a short while.Discussions on the technical advantages and disadvantages of different brands were dissected threadbare with each one of us holding forth on which motor-cycle was the best and why. By and large, we were all hooked onto Bullet and Jawa, which to us, were ultimate symbols of macho. A few of our friends never hid their pride at owning a BSA American which was far beyond our hopelessly limited finances. But dreams don't cost a dime and our imagination never failed us on what it would be like to ride a BSA American or a Harley Davidson.

Our obsession ensured we were exceptionally good drivers which was much before the government decided in its limited wisdom that driving without helmet was unsafe. Whenever friends loaned a Bullet or a Jawa, we would go for long rides out of the city as if we were the real owners. The bike was loaned but our prides were not. They were our very own. We were good even if the machines were uncharitably dubbed as mean. The smell of an engine stirring to life and its strokes was music to our perennially pricked ears. If nothing else, we would park ourselves in front of a bike showroom and soak in those brand new machines wondering when would the good day dawn when we would own one.

While driving, however, our heads would be firm on our shoulders. Rash driving was out of question. Rather we thought there was a greater sense of fulfilment in driving at cruising speeds. Driving was a pleasure we wanted to cherish. Only on one occasion I remember the two of us had gone to a place some 70 kms away to meet a friend. That visit turned out to be more exciting than we had thought. We ran into some bootleggers there who were considerate enough to offer their lethal concoctions to us in rusted pan masala tin boxes. It was only when they started climbing on us in their drunken stupor that we realised it was time to take a quick exit. That was the only time when we drove so fast, we were practically standing on the accelerator. If we didn't met with an accident it was more by fluke than judgement.The one thing we were unanimous about big bikes was there was no need to tonk horn. The mere look and the engine sound was enough to scare people out of the way. The big bikes usually called for wearing shoes because for a vehicle like Jawa the kick-start was hard and tough. The bike was mostly used by hefty "doodhwala bhayyas" carrying large milk cans on either sides. The Bullet was a slightly more polished variety because of its regal appearance and the quality of drive it offered although a kick backlash spelt a potential disaster.

As it happened in other spheres of life, the bike world underwent a cosmetic transformation from early eighties when the 300 cc machines were replaced by the 100 cc and 150 cc varieties like Yamahas and Hondas. For us, hard-boiled for years on heavy machines, these were poor variants -- the same difference between gold and rolled gold. We drove the newer, leaner machines but that sense of satisfaction always eluded. Sadly, the heavier ones were almost edged out of the competition. Jawa stopped production after mid-nineties while Bullet has become a no-no because in terms of fuel it is not as cost effective. In our estimate, however, the gratification took precedence over the cost.

The Bullet also known as Royal Enfield is now only a few owners' pride and many others' envy. I have often seen 100 cc bikers casting jealous glances at an occasional Bullet driver whizzing past them. A Harley Davidson or other such brands can be found with only the rich and enthusiasts like Dhoni and John Abraham to whom money is not an inhibiting factor. Bahut naainsaafi hai.

Today, these motor cycles are pages almost lost in history. After all, we live in times when life itself is a crazy ride and nothing is guaranteed.

|

| Friend-colleague Sharad Rotkar on a Bullet. |

Our obsession ensured we were exceptionally good drivers which was much before the government decided in its limited wisdom that driving without helmet was unsafe. Whenever friends loaned a Bullet or a Jawa, we would go for long rides out of the city as if we were the real owners. The bike was loaned but our prides were not. They were our very own. We were good even if the machines were uncharitably dubbed as mean. The smell of an engine stirring to life and its strokes was music to our perennially pricked ears. If nothing else, we would park ourselves in front of a bike showroom and soak in those brand new machines wondering when would the good day dawn when we would own one.

While driving, however, our heads would be firm on our shoulders. Rash driving was out of question. Rather we thought there was a greater sense of fulfilment in driving at cruising speeds. Driving was a pleasure we wanted to cherish. Only on one occasion I remember the two of us had gone to a place some 70 kms away to meet a friend. That visit turned out to be more exciting than we had thought. We ran into some bootleggers there who were considerate enough to offer their lethal concoctions to us in rusted pan masala tin boxes. It was only when they started climbing on us in their drunken stupor that we realised it was time to take a quick exit. That was the only time when we drove so fast, we were practically standing on the accelerator. If we didn't met with an accident it was more by fluke than judgement.The one thing we were unanimous about big bikes was there was no need to tonk horn. The mere look and the engine sound was enough to scare people out of the way. The big bikes usually called for wearing shoes because for a vehicle like Jawa the kick-start was hard and tough. The bike was mostly used by hefty "doodhwala bhayyas" carrying large milk cans on either sides. The Bullet was a slightly more polished variety because of its regal appearance and the quality of drive it offered although a kick backlash spelt a potential disaster.

As it happened in other spheres of life, the bike world underwent a cosmetic transformation from early eighties when the 300 cc machines were replaced by the 100 cc and 150 cc varieties like Yamahas and Hondas. For us, hard-boiled for years on heavy machines, these were poor variants -- the same difference between gold and rolled gold. We drove the newer, leaner machines but that sense of satisfaction always eluded. Sadly, the heavier ones were almost edged out of the competition. Jawa stopped production after mid-nineties while Bullet has become a no-no because in terms of fuel it is not as cost effective. In our estimate, however, the gratification took precedence over the cost.

The Bullet also known as Royal Enfield is now only a few owners' pride and many others' envy. I have often seen 100 cc bikers casting jealous glances at an occasional Bullet driver whizzing past them. A Harley Davidson or other such brands can be found with only the rich and enthusiasts like Dhoni and John Abraham to whom money is not an inhibiting factor. Bahut naainsaafi hai.

Today, these motor cycles are pages almost lost in history. After all, we live in times when life itself is a crazy ride and nothing is guaranteed.

No comments:

Post a Comment